Teetering on Hell’s Doorstep

Steve Gerkin

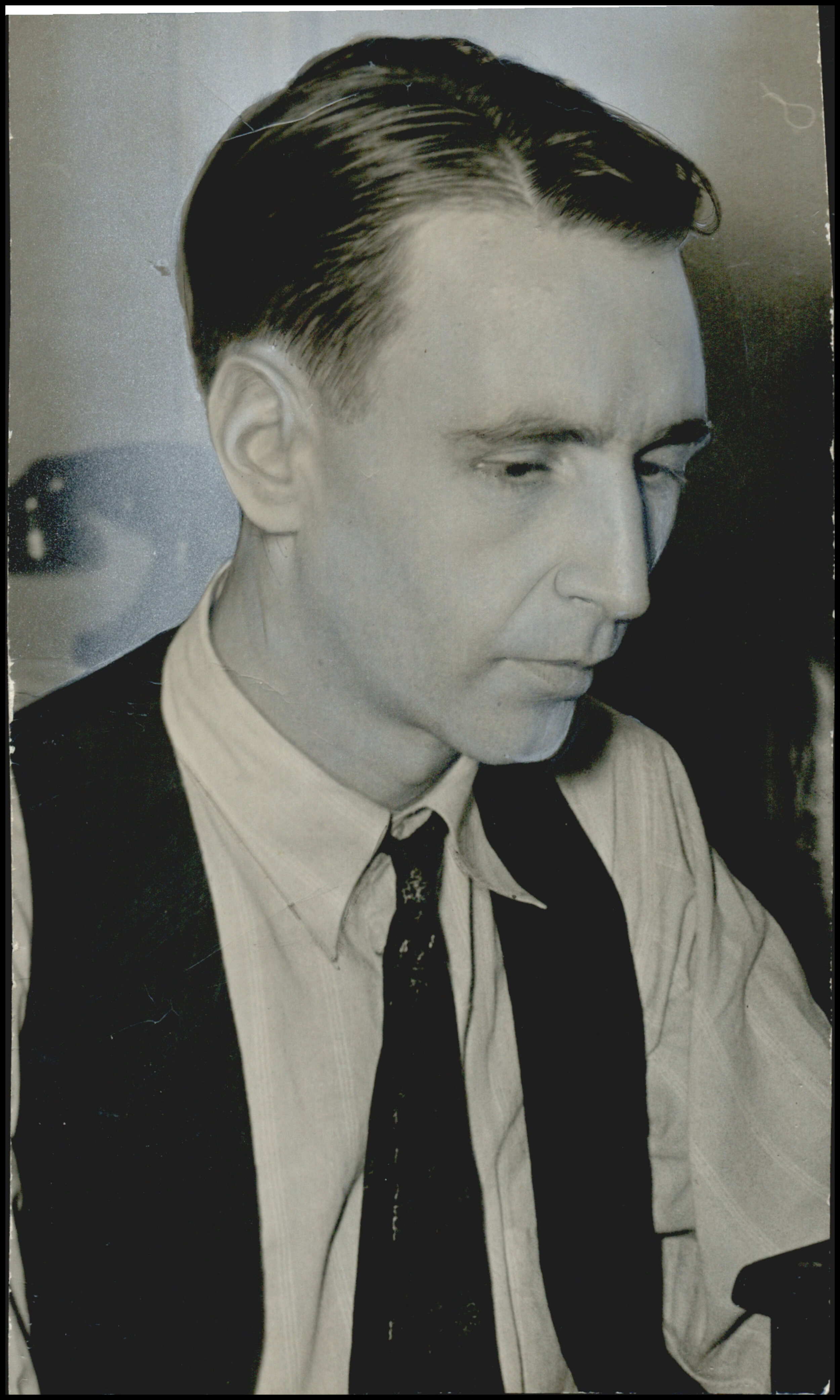

Jim Thompson at his desk in Oklahoma City as the Director of the Federal Writer’s Project (WPA) circa 1938 (Photo courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society)

"I took one last look at Jake before I left the room. Ruthie had almost sawed his throat out with one of his own razors. Scared, you know, and scared not to. Angry because she was scared. It looked a lot like the job I'd done on Fruit Jar."

Jim Thompson, Savage Night, Lion Books, 1953

Jimmie Thompson convulsed on his bedroom floor; blood poured out of his mouth. His heart raced and beat irregularly. The doctor quickly assessed the 19-year-old's health: complete nervous collapse, tuberculosis, and alcoholism with delirium tremens.

Heralded by many as the premier crime novelist, Thompson’s name would someday become synonymous with sinister stories in dime-novels. He would publish 29 original books and be named “the best suspense writer, bar none” by The New York Times. But it was his young, brutal and complicated young life in Texas, Oklahoma and Nebraska that staged the success he found later on. His novels would become favorites of the author Stephen King, who said, “The guy was absolutely over the top. Jim didn’t know the meaning of the word stop.

Creative Arts Company’s Black Lizard series began reprinting Thompson’s work in the 1980s. Within his introduction of Savage Night, Barry Gifford defines Thompson’s work as a “bleak, corrupt world, where male characters manifest schizophrenic behavior, haunted by an unpredictable demon.”

An Itinerate Beginning Affected His Soul

Jimmie Thompson started life in 1906 on a kitchen table above the cell-block of the Caddo County Jail in a desolate berg called Anadarko on the south-central plains of the soon-to-be state of Oklahoma.

His father, James “Big Jim” Sherman Thompson, served as a deputy in Indian Territory. Outlaws shared space there with the relocated nations of The Five Civilized Tribes. They congregated in the caves, gullies, and underbrush that bordered Indian Territory and the United States; white criminals were often immune from extradition and couldn't be charged in Indian courts. U.S. marshals called the area, "Hell's Fringe."

Even local peace officers shifted to the dark side of the law. When Jimmie was six, Big Jim was charged with embezzlement and escaped on horseback for Mexico. It was the first of many times he would leave his family. During these separations, Jimmie’s mother, Birdie and her children lived with her parents in Burwell, Nebraska. That’s where Jimmie learned about hell. His Grandma Myers’ prairie fundamentalism created a sense of unavoidable doom. After one of her country revival meetings, he writes in the semi-autobiographical novel Bad Boy, “I lay shivering in my dark bedroom, I was too terrified to sleep." In Heed the Thunder, he compared his grandmother’s hairstyle to a cow chip.

In contrast, Grandpa Myers soothed Jim's fears with puffs from his Pittsburg stogie. He spun tales as the two played cards, hunted anything that moved and sipped on hard cider. As a run-up to Jimmie’s first day of school, Grandpa gave the first-grader a little "pick-me-up," saying it was "a cold preventative that purified the blood." Jimmie openly regretted, later in life, that he had acquired an early taste for alcohol at the hands of his elder relative.

Off and on, Big Jim reentered the family picture with bombastic flair befitting an outlaw deputy. "You're bringing these children up in ignorance,” he told Birdie when Jimmie was eight years old, Punching up his vitriol, he added, “By the age of four, I could name all the presidents." He bought encyclopedias and letters of presidents, making Jimmie read them aloud and peppering him with questions. He drilled him in accounting and coached him in political science.

Jimmie preferred to spend hours writing small bits of fiction. He was shy, rheumatic-legged and suspicious of people; the antithesis of his bullish, athletic and charismatic father. Robert Polito in his Thompson biography, Savage Art, says the sudden, intense interest from his father created a sense of shame that stayed with Jimmie throughout his life, as did his anger toward his father, who kept the family close to starvation with entrepreneurial endeavors—failing as an owner of a bush-league baseball team, a garbage hauling business, and a turkey farm.

As Grandma Myers had reminded the children, "You're not sent to hell, but punished right here on earth."

Writing Became a Constant Companion

Jimmie began his freshman year at Polytechnic High School in Fort Worth. Lacking respect for his Texas-born teachers with their conceited self-images, Jimmie failed his English class. He misled his father with the impression of diligent, nightly studying. Instead, the teenager was writing short squibs. At 14, Jimmie received his first paycheck of several dollars for an article published in True Detective. Although his squibs continued to appear in pulp periodicals, the checks were small, which Big Jim used to take potshots, saying the paltry payments reflected his son's measly talent.

Big Jim demanded his son find a job, Jimmie donned a fedora, dangled a cigarette from his mouth, and swaggered into the offices of the Ft. Worth Press. The nearly-15-year-old leaned over desk of the editor, who glanced at the freelance check stubs presented by the Bogart-imposter. Standing up, he snatched Jimmie’s hat and cigarette, and asked, "Would you like to sit down?"

The youngster sank into a chair. Impressed that Jimmie had sold bits to magazines, he softened, saying, "That's very good. I've never been able to sell as much as a two-line joke to a magazine." He arranged for the teenager to work after school and at 8 a.m. on Saturdays. Jimmie's duties were copy boy, gofer, and occasional typist. The $4 a week was barely enough to cover his expenses.

During his time at the Press, editors treated Jimmie with respect. They gave him opportunities to observe the means of the newspaper business, and he worked of his own accord. Gone was his greasy hairstyle, his tight pants. He quit smoking, shined his shoes, cleaned his fingernails, and developed a polite matter. In Bad Boy, Thompson said, "As long as I was treated properly— and my standards in the matter were high—I treated others properly." His short story writing continued. Big Jim was blind to the fact that his son was thriving. He wanted Jimmie to focus on school and made him quit the paper.

In and out of school, continuously suspended, the disobedient teenager started bell hopping at the Hotel Texas, earning a guaranteed $15 a week, and, frequently, pulling in $300 in weekly tips. It was the Roaring Twenties. He learned how to cope with rich patrons and grimy crooks. Jimmie worked seven days a week, 11 p.m. to 7 a.m. Drinking unfinished drinks of patrons, he satisfied his penchant for alcohol. On the job, he struck up friendships with low-lifes who would, someday, find their way into his books. The FBI killed one of the fellows with whom he hopped bells. Another became crippled while blowing up a safe. Several committed suicides, and another overdosed on drugs, causing him to bite his tongue off and drown in his blood. A hotel regular, thug and con man Allie Ivers, frequently stole baggage from the holding room and held sway on a vulnerable Jimmie. Local hoodlums and other alter-egos taught him tricks— such as the "grift" (a short con) and "rat-holing" (palming an occasional twenty)— and appeared as characters in Texas by the Tail, Recoil, The Grifters and Bad Boy. The fictional personalities of former associates create webs of deceit that suck the already uncomfortable reader into the treacherous downdraft of his writing's gloom.

After his hemorrhagic breakdown at the beginning of his senior year at Polytechnic and four months of convalescence, Jimmie found himself on a highway out of Ft. Worth with his thumb in the air, headed for West Texas. In Now and on Earth, Thompson wrote, “On the night my high school class graduated I was seated on a generator, far out on the Texas plains.”

Over the next three years, Jimmie dismantled oil derricks, dug holes for highline towers, and night-guarded the construction of a pipeline while writing atop a table rock overlooking the Pecos River. He inadvertently destroyed most of those writings when his old nemesis, delirium tremens, returned. As he walked past tumbleweeds, his imagination saw images of rattlesnakes and spiders that came straight for him, some disintegrating under his boots, some not. With that, Jimmie left the desert and went back to Ft. Worth in 1928 and the Hotel Texas.

1930s postcard of the Hotel Texas, Ft. Worth, Texas

Despite the long hours, chaos and booze and cocaine-sniffing of the Hotel Texas, his crime-story writing success continued. An editor, a University of Nebraska alum, suggested Jimmie could improve his skills at college. Deciding it was now or never, he left the hotel life for school in Lincoln, Nebraska. The editor found him a loan, and Jimmie worked odd jobs and ate stale bread to support himself. There he met the only love of his life, Alberta Hesse, at a dance. They eloped, creating a chasm between her family and Jimmie.

Jim and Alberta Thompson, early 1940s in California

Early in their marriage, she became pregnant. Penniless and in need of a job, Jimmie said goodbye to his wife and settled into a railcar headed south for Texas oil with some new hobo- friends named Jiggs and Shorty. "Jimmie's tendency to throw himself into jobs and situations was against his nature," his sister Maxine told Polito. "It seemed he could muster the courage to venture into possible self-destructive scenarios— like his train-riding hobo phase— always, searching for writing material."

Leftist Political Core Realized

His time in the oil fields laid another foundation. Shortly after his arrival in West Texas, he met union organizer Harry McClintock and became a member of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) union, called Wobblies. McClintock loaned him The Manifesto of the Communist Party. Thompson listened to Woody Guthrie and others, who played folk songs of protest. He read Karl Marx, claiming later to his writer-friend Gordon Friesen, that, “reading Marx was my first real education, gave me the words to understand my life.” And as many intellectuals of the Depression Era did, he joined the evolving Communist Party in 1935.

When Jimmie's enterprise of unplugging a former oil well blew up, it opened the door for his next break. He headed to Oklahoma City for a rendezvous with Alberta and his yet-unseen newborn daughter, Patricia, and learned of a Workers Project Administration (WPA) offshoot called the Federal Writer's Project (FWP). The director of the Oklahoma FWP was William Cunningham, a native of Okeene, Oklahoma (IT). Cunningham authored books about the virtues of atheism and was a card-carrying member of the Communist Party. He had taught Marxism economics at Commonwealth College, a leftist-leaning labor institution in Mena, Arkansas, and stirred controversy as an English professor at the University of Oklahoma. His novel The Green Corn Rebellion (1935), immortalized an anti- war revolt staged by rural Oklahomans in the early 1900s.

Fellow members of the Communist Party and writers for Thompson’s Federal Writer’s Program (WPA) in Oklahoma City during the late circa 1937

Active in the late 1930s, the FWP and Cunningham used funds from President Roosevelt's WPA to pay his twenty-some writers, who mostly wrote guide books to encourage tourism. Although the majority hailed from the relief rolls and proved to be "dead wood," Cunningham counted Louis L'Amour and Gordon Friesen among his recruits. Both would have writing legacies into the next century; L'Amour for his frontier stories, and Friesen for his Broadside song magazine, which published early songs by folk revival singers, including Bob Dylan.

Jim Thompson fit right in. Thompson quit his Party affiliation in 1938, around the time he half- heartedly applied for hire with the WFP. Director Cunningham enthusiastically brought him into the fold. Eighteen months later Jimmie became the Oklahoma director for the Federal Writer's Project, a job that ended over Jimmie's insistence to publish a book of the state's labor history. The contents of the publication infuriated state and federal politicians. Upon its controversial release, Thompson resigned after less than two years on the payroll, and the office closed.

Famed Writing from the Plains of the Midwest to the Depths of Série Noire

At the end of a one-year grant-in-aid from the Rockefeller Foundation, the Thompsons moved from Oklahoma City to San Diego. A book deal fell through. Unfazed, Jim worked at an aircraft plant and wrote several detective stories. This netted him enough money to take him to New York City on a bargain-rate bus to pitch a book. It was November of 1941.

Rejected by several publishers, Jim returned empty-handed to San Diego, where his alarming drinking binges matched his productivity: a novel in five weeks, six true crime features in one month. He dried out in San Diego sanitariums 27 times in three years. Thompson would joke, "I got nothing but temporary sobriety and enormous bills."

Still convinced New York held the key, he returned to the city, while his family waited in San Diego for the thumbs up to join him. They arrived in October, moving into an apartment near Jimmie's sister, Maxine. His agent, Ingrid Hallen, arranged a meeting with Arnold Hano, editor of Lion Books. Hano supplied the post-World War II demand for paperback originals. Asked the difference between Lion and other publishing houses, he recalled, “Without really knowing what we were doing, we were developing the whole série noire kind of a novel to a greater degree than anyone else had, or was.” The big sheepdog, as Hallen described the hulking Thompson, created the first chapters of the classic The Killer Inside Me for Lion in two weeks. The Killer featured a New York cop taking up with a prostitute, then killing her. Thompson’s noir writing style began in earnest at the age of 43. His stories brought readers into his characters disturbed psyches, terrifying them with gross, criminal behavior, trapping them with their edgy, snaky tendencies. British critic from Central Saint Martins college Nick Kimberley described Thompson's accursed and self-destructive characters as "living in a godless world and for whom murder is a casual chore."

Thompson Blossoms in early 50s

Savage Night - a “dime-store novel - published in 1953 during the Post World War I I reading frenzy. Jim Thompson became a successful noire crime writer, publishing 12 of his novels within a three-year period from 1952-54 with Lion Books.

The isolation of Thompson's characters mimicked his actual detachment. The turmoil and tragedy in his life often paralleled his storyline text. "Whatever his problems were, Jim worked them out in his novels," advised Hano, who proved to be Thompson's savior. Between September 1952 and March 1954, the Thompson/Lion combination produced 14 books, including The Criminal, Hell of a Woman, The Kill Off and other career-enhancing home runs like Savage Night, a syndicate-based novel that introduced the world to Charlie "Little" Bigger, a smallish, contract murderer, who has a late night meeting with a hardened criminal, “Fruit Jar.”

The trouble with killing is that it's so easy. You get to where you almost do it without thinking. I had him pull up there in the shadows of the elevated subway, and I said, "I'm sorry as hell Fruit Jar. Will you accept an apology?

He stuck out his hand, "Sure, kid." I stuffed his hand between my knees. I snapped the knife open.

His eyes got wider, and his mouth hung open like the mouth of a sack, and the slobber ran down his chin, thick and shiny.

I gave it to him in the neck. I damned near carved his Adam's apple out. I took the silk handkerchief out of his breast pocket, wiped my hands and the knife, and put the knife in his pocket.

Then I shoved him down on the floor of the car and caught the train into town.

Harvard-educated poet and University of Iowa Writer's Workshop professor Geoffrey O'Brien famously nicknamed Thompson a "Dimestore Dostoevsky." Jim Millaway, a Tulsa collector of all-things-Thompson, asserts that Jim, "Wrote about 'real' people, attracting a growing readership to the new pleasures of pulp fiction," adding, "Thompson accelerated the pace of his stories, grabbing the reader with compelling scenarios."

Thompson in his later years

Some say Jim Thompson was a 'big teddy bear' whose inner-rage roiled just below the surface and maintained a somewhat fantastical existence with alcohol at its core. He and his characters, often, mirrored similar characteristics. When offended, the writer rebuffed perceived insults by vengefully slashing his violators with the keys of a typewriter, depicting them as story characters who acted out their deceitfully tranquil, daily routines, and swiftly, unexpectedly became butchers of human flesh and spirit. His success also attracted the attention of Hollywood filmmakers.

A tumultuous relationship with Stanley Kubrick kept Jim upset and drunk for years. It also kept him financially afloat, barely. The textual grenades he threw at lightly-veiled, fellow professionals, often, undermined the demand for his writing; revenue fluctuated accordingly.

With dollars scarce in 1976, the Thompsons moved into a “real dump,” according to a daughter. It was a second-floor, shotgun style apartment, just down the street from the Hollywood Bowl. Months later, Thompson suffered a massive heart attack that placed him in a four-day coma. Doctors predicted he would not survive. When he proved them wrong, they called him “Superman.”

Superman, Dostoevsky, Bogart. He was all of these men, and he was none of these men. In his soul he remained the kid at the editor’s desk of the Ft. Worth Press: bruised by disrespect and thriving when offered dignity. In his final days, Thompson could smoke only when a family member was present. Raising two fingers as if holding a cigarette, his unfiltered Pall Mall was placed in the V of his stained fingers. It made him smile from the confines of his bed.

A determined Thompson rallied to attend Christmas at daughter Sharon's home in Huntington Beach. Jim ran through all his old stories - same scenes, same words. He made a simple request to drive to the shore. Quietly, he sat in the car, watching the ocean waves crash against the sand and listening to the hiss on their way out.